The covid-19 pandemic has led to tragic personal loss and wreaked economic havoc on a huge scale across the globe. On the economic front in Europe, the ECB’s estimates for Eurozone GDP this year range as low as -12%. Governments have rushed to support their people and economies through a wide range of different measures. Central Banks including the ECB have also joined the battle offering lending facilities at ultra-low interest rates and promising secondary market purchases of large amounts of corporate bonds as well as a significant proportion of the €1-1.5trillion government debt likely to be issued this year to pay for national European support programmes. Banks so often blamed for past crisis are now seen as part of the solution to this one and have been enlisted by national authorities to channel some €1.5trillion of Eurozone government guaranteed lending to where it is needed, fast.

To help them do this, the flexibility built into the prudential regulatory framework has been triggered allowing banks to draw down on their substantial capital and liquidity buffers. These had been built up after the last financial crisis against such an eventuality as we are now facing. Recognising that scarce human resources might be needed elsewhere banks have also been allowed to postpone certain other obligations and pragmatic solutions have been found to permit markets to continue functioning in the new lockdown environment.

More recently the European Commission has sought to provide banks with additional lending capacity by introducing targeted changes to the existing Capital Requirements Regulation. These are a mixture of substantive and timing changes. Amongst other measures, substantive changes have been made to ameliorate the capital impacts from IFRS 9 which governs the accounting treatment of provisioning for prospective credit losses and also allow the exclusion of banks’ holdings of Central Bank deposits from their leverage ratio exposure measure. The EC has also sought to bring forward beneficial measures including the application of favourable capital treatments for software assets and SME and infrastructure lending which were originally slated to come into force next June.

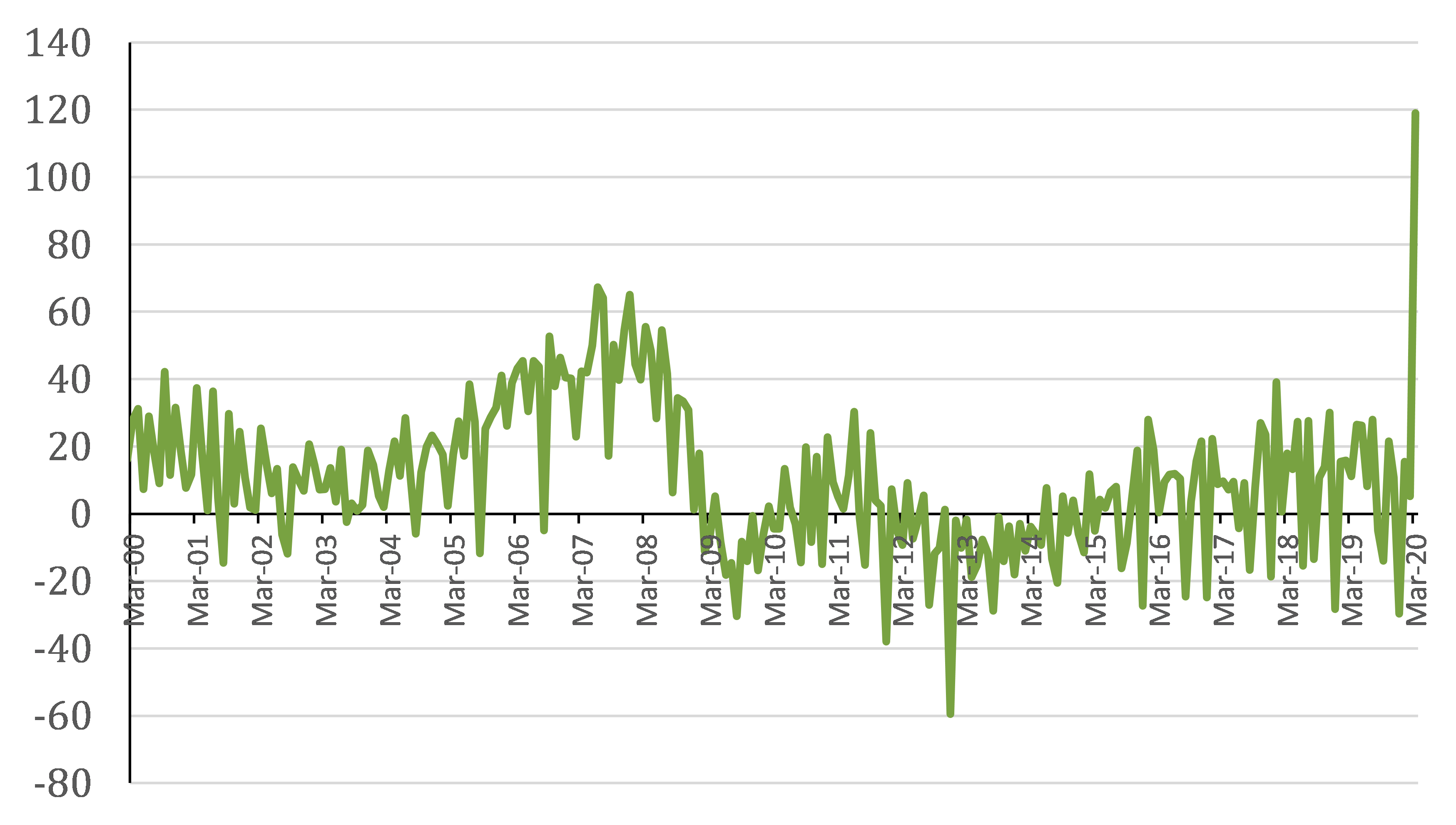

The question is are these changes going to be sufficient to furnish banks with enough capacity to provide the support to their customers that is going to be needed in the coming downturn, let alone the recovery? We are not so sure that they will. According to ECB statistics, demand for funding in March - before the full severity of the economic downturn has been felt - was already at a record high with non-financial corporations borrowing nearly €120bn, more in that month than the whole of last year and higher than at any time in the last twenty years. ECB lending surveys point to similar very strong demand in the coming months.

Net lending to euro area corporates (EURbn)

Source: ECB Euro area statistics: BSI.M.U2.N.A. A20.A.4.U2.2240.Z01.E

The ECB has estimated that banks using their capital buffers and changing the capital composition of their so-called pillar 2 requirement will free up €120bn of capital, enough to support €1.8 trillion of additional lending. Yet a quarter of this depends on the banks managing to issue new AT1 or T2 debt instruments and despite a few banks recent foray into the market this will take some time. Moreover, it is far from clear whether this lending capacity is truly new or includes substantial committed facilities which will need to be fully capitalised once they are drawn down and come onto banks’ balance sheets. Banks may also be unwilling to fully run down their capital buffers for fear that this could trigger restrictions in making payments on their AT1 debt which could cause a significant disruption in this market and negatively impact on the availability and pricing of future capital raising.

A recent BIS bulletin from the 5th May also raises questions on the reliability of the estimated lending capacity in the EU. It suggests that in a severe adverse (but in this case realistic) scenario releasing bank buffers would only generate between $1.1 and $2.6 trillion dollars on a global basis suggesting that the capacity figure in the Euro area may be overestimated.

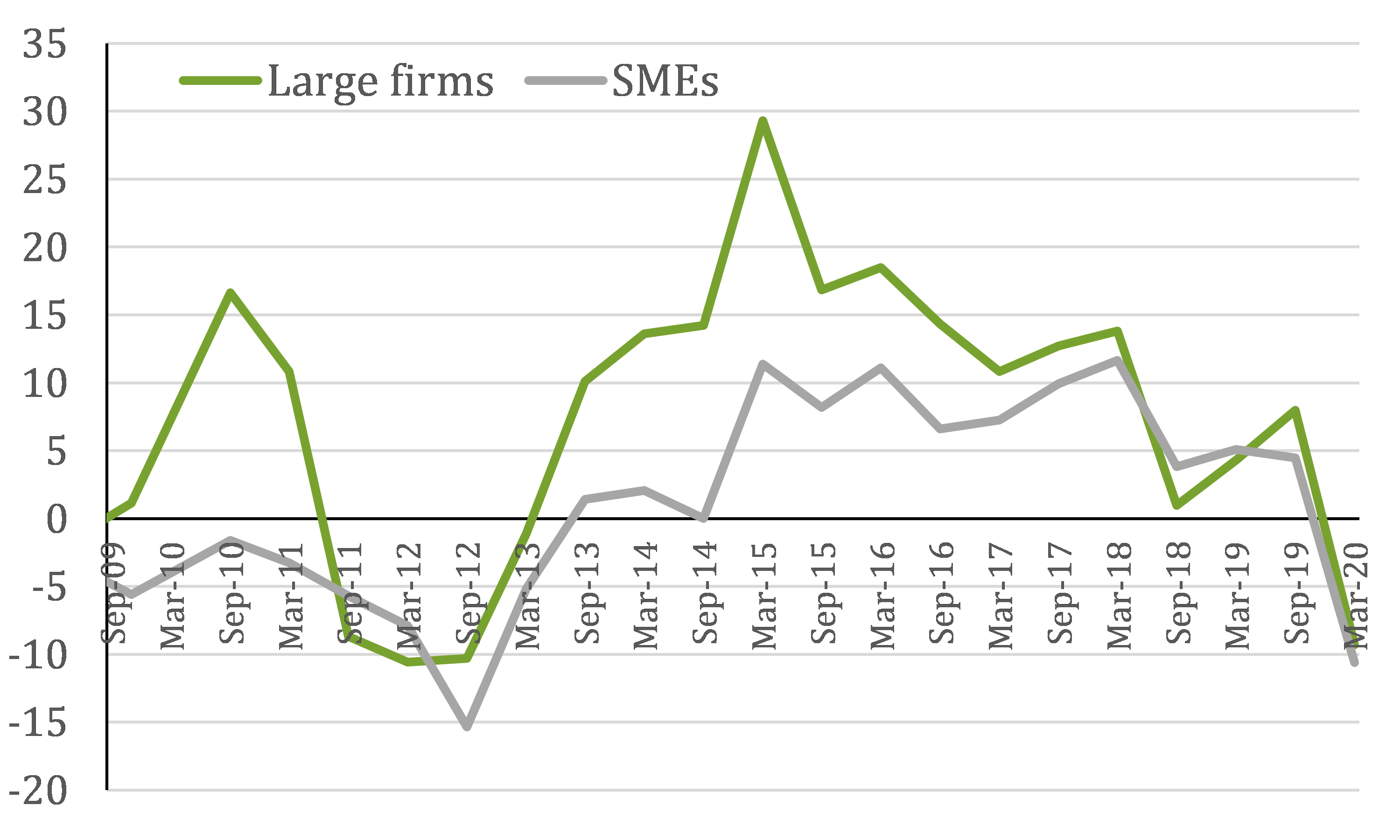

It is perhaps not surprising therefore that the ECB’s SAFE survey conducted between March and April this year and which covers expectations for access to finance in the Eurozone in the next six months is sending a significantly negative signal.

Businesses expect a sharp decline in bank lending for the next 6 months

Expected availability of bank loans according to euro area large firms and SMEs (for the next 6 months)

Source: Source: ECB SAFE survey, Question 23. Net (increased minus decreased responses)

- Excluding not applicable responses. Horizontal axis shows the month in which the survey was undertaken

The other problem with relying on the ECB’s estimate is that it does not appear to take account of the fact that all the extra lending will only be possible if banks have sufficient capacity to finance it under both their non risk based leverage ratio measure and their risk based capital requirements. Whereas under risk based capital requirements banks are not required to hold capital against government debt (including the relevant portions of most government guaranteed loans) this is not the case for the leverage ratio measure which requires such exposures to be included at their full nominal value. As a result, banks wanting to make markets in government debt or advance government guaranteed loans may find that they have insufficient headroom in their leverage ratios to do so.

In summary our concern is that the capacity available to banks in terms of capital headroom will be insufficient to meet the demand for it. The solution to this is to make further targeted and time limited changes to the EC’s CRR proposal. We have made several suggestions including ensuring that the benefit from an exclusion of Central Bank deposits from the LR exposure measure is effective now rather than in twelve months’ time. We also think that consideration should be given to the exemption of government guaranteed loans from the leverage ratio for a limited time. Both these adjustments have been made in several other jurisdictions and would strike an appropriate balance between providing banks with additional lending capacity and ensuring their continued robust solvency in the current stressed environment.

Regrettably, the need for speedy legislative change and entrenched national positions has led to a reluctance to broaden the proposal currently on the table in the manner required. As has been the case during this crisis, EU Member States, while agreeing the common challenge have struggled to formulate solutions acceptable to all. The last time there was a crisis Europe was, by common consent, both late and timid in its solutions. Let us hope that history is not repeating itself.